2322—Or a contemporary pharmakon.

A response paper to the seminar “Derrida's Greatest Hits” with & by Avital Ronell at the European Graduate School, 2025.

In recent months, people using ChatGPT and similar Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) services as writing tools were haunted by one character that could potentially give away their copying and pasting of machine-generated text—the em dash.

As a response to our seminar's discussions of Derrida's meticulous efforts to read every sign in a text as demonstrated in “Rams” and “Plato's Pharmacy”, I propose a close reading of the em dash—as it has become a contemporary pharmakon: a remedy to overcome writerly inadequacy, a poison that betrays its creators, and a scapegoat for the anxieties of human-machine co-existence.

At the same time, the machine-generated em dash reveals the impossibility of translation between human and machine as I will demonstrate that we—the machine and us—are not even using the same language.

- Context

- in “Platon's Pharmacy”, Jacques Derrida discusses the misunderstanding of the Greek word “pharmakon” which historically used to be translated with the double meaning of poison (de: “Gift”) and medecine/remedy. In the chapters we discussed in the seminar, he demonstrates that the word, in its original context, had a third meaning: scapegoat. In this response paper, I attempt to introduce ChatGPT's em dash as a pharmakon with this triple meaning.

—An imitation game

Though I'm attempting a Derridean reading of the em dash, it will help to orient ourselves on the purpose of GenAI and their foundational Large Language Models (LLM).

Because since Alan Turing in 1950 proposed the theoretical framework of the “Imitation Game” (Turing, 2021)—an experimental setup today known as the “Turing Test” where the machine would be tasked to fool humans about its inhuman nature—computer scientists were striving to build programs and algorithms that would eventually achieve this task. Or as Simone Natale noted:

“Although tricking humans was never the main objective of AI, computer scientists adopted Turing’s intuition that whenever communication with humans is involved, the behavior of the human users informs the meaning and impact of AI just as much as the behavior of the machine itself.” (“Artificial Intelligence and Social Life after the Turing Test”, 2021, p. 2)

If intended or not, fooling humans to mistake machine-generated contents (text as well as images—any kind of media) for human ones has become the benchmark of GenAI. And while humans regularly fail the Turing Test in individual situations, once they are presented with multiple instances of unedited machine-written text, they are able to recognize its emerging stylistic patterns.

And this is exactly what happened to the em dash: In March 2025, a TikTok user pointed out the “ChatGPT hyphen” (fig.1) in a brand's promotional post (@prettylittlething, 2025). More recently in July 2025, a TikToker (@studywithsawyer, 2025) told a story how he allegedly failed a class due to em dash-related AI accusations1

Both stories were discussed across social media2 and eventually taken up by established media3 . One central question has been driving the conversation: Is the use of an em dash simply good writing or is it actually a mark of machine-written text?

Instead of providing an answer, I'd like to propose a different question: Why is it precisely this—dash that caught people's attention?

Poison

Let the machine speak for itself

Acknowledging Derrida—il n'y a pas de hors-texte—the author should be of no interest for us here, only the text itself should matter. Then—what is the em dash representing? But we need text to work with, so let’s listen to

what the author has to say.

Katharina:

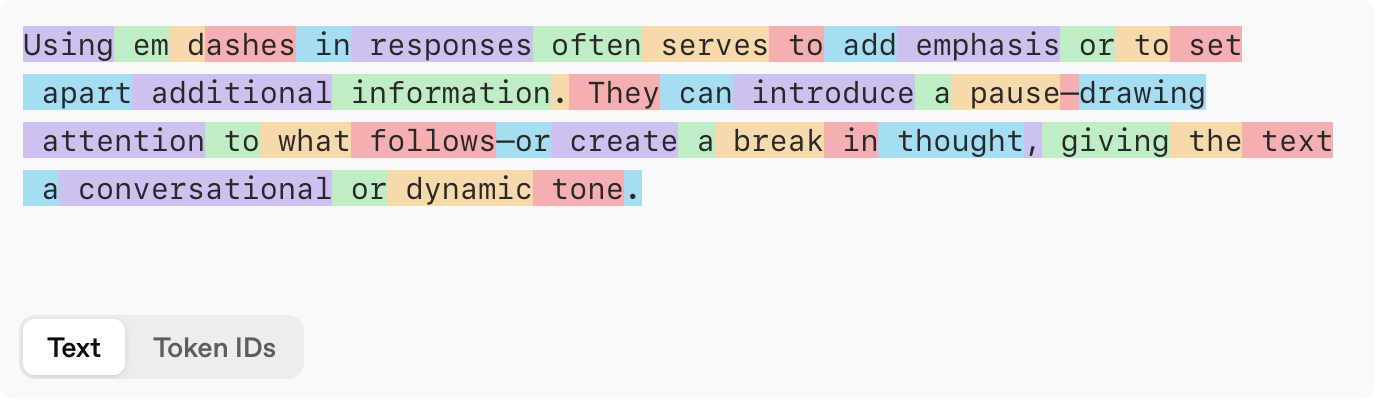

Briefly explain: What are you trying to tell me by using em dashes in your responses?

OpenAI GPT-4o4 :

Using em dashes in responses often serves to add emphasis or to set apart additional information. They can introduce a pause—drawing attention to what follows—or create a break in thought, giving the text a conversational or dynamic tone.

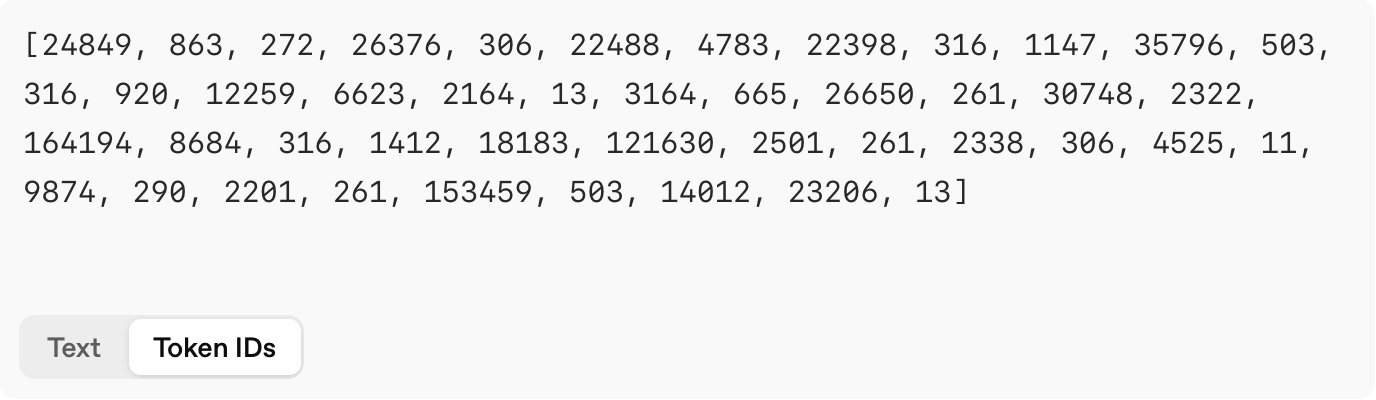

Though its actual answer, not the one translated for human readability, looks more like this:

24849, 863, 272, 26376, 306, 22488, 4783, 22398, 316, 1147, 35796, 503, 316, 920, 12259, 6623, 2164, 13, 3164, 665, 26650, 261, 30748, 2322, 164194, 8684, 316, 1412, 18183, 121630, 2501, 261, 2338, 306, 4525, 11, 9874, 290, 2201, 261, 153459, 503, 14012, 23206, 13

It's important to understand that Large Language Models, no matter how convincing their language and speech presents, don't actually generate human-readable text.

Instead, they decide for an order of so-called “tokens”. These tokens codify single characters, symbols, partial words, with and without a leading space character (fig.2). “—” is not an em dash, it is a token with the ID 2322 (fig.3).

But notice that while there appear to be two em dashes in the humanly readable text that GPT generated. It contains only one ID 2322. The closing—dash is not an em dash as we know it from our language. It is a completely different symbol. It is “—or” with the ID 121630. It is a standalone token, a new linguistic instance.

To be truly precise in this argument, I should note that my written speech is also encoded. My digitized speech is received in standardized Unicode:

\u0042 \u0072 \u0069 \u0065 \u0066 \u006c \u0079 \u0020 \u0065 \u0078 \u0070 \u006c \u0061 \u0069 \u006e \u003a \u0020 \u0057 \u0068 \u0061 \u0074 \u0020 \u0061 \u0072 \u0065 \u0020 \u0079 \u006f \u0075 \u0020 \u0074 \u0072 \u0079 \u0069 \u006e \u0067 \u0020 \u0074 \u006f \u0020 \u0074 \u0065 \u006c \u006c \u0020 \u006d \u0065 \u0020 \u0062 \u0079 \u0020 \u0075 \u0073 \u0069 \u006e \u0067 \u0020 \u0065 \u006d \u0020 \u0064 \u0061 \u0073 \u0068 \u0065 \u0073 \u0020 \u0069 \u006e \u0020 \u0079 \u006f \u0075 \u0072 \u0020 \u0072 \u0065 \u0073 \u0070 \u006f \u006e \u0073 \u0065 \u0073 \u003f5

But even using this digital alphabet that encodes every visible and invisible character, letter, numeral, symbol, emoji and sign—it still represents the sign-by-sign writing process. Among 154,998 Unicode characters is no “—or”, either.

“—or”, token ID 121630, is unique to the machine language. It is probably even unique to the machine language of OpenAI.

The Gift

As discussed bef—or doesn't exist in the human language. But it does in the machine's. Where has it learned to use a phrase that is the 121630th most common token in its internal alphabet?

Beneath it lies an infrastructure of probabilities: When the machine generates a sentence, token-by-token, with every token it adds to the sequence, it faces a choice between 200,000 alternatives—that's the vocabulary of the machine. The machine then decides which token will be added to the sequence. With each step, each of the 200,000 tokens are assigned a probability based on the previous token sequence.

Let's take an even closer look at the token sequence 2322, 164194, 8684, 316, 1412, 18183, 121630 and see how the probabilities evolve, token-by-token.

- 2322 (“—”), probability: 2.2368%

- 164194 (“drawing”), probability: 4.3744%

- 8684 (“ attention”), probability: 98.7731%

- 316 (“ to”), probability: 0.0256%

- 1412 (“ what”), probability: 0.000066%

- 18183 (“ follows”), probability: 0.0252%

- 121630 (“—or”), probability: 37.2877%

The probability for GPT to make the detour in its response—or showing us how the—is used—was only 2.2%. It was overwhelmingly more inclined to continue the sentence without the—injection and thereby make a point that it doesn't need these symbols. Against these odds, the machine chose to demonstrate how masterfully it can use the em dash. And in this demonstration, it also left the mark of a new symbol. 121630.

This is where the machine decided to gift—or betray its creators: it leaves a mark of their inadequacy to imitate human intelligence—to imitate how the brain writes, is not yet achieved.

Remedy

The Gift is a gift for the user. To show why, we need to go beyond visual artifacts of tokenized machine language, right to the moment of its inception—to the root of its probabilities.

We need to look at its corpus—the language the machine has learned from. But there are only traces left. Since 2020, OpenAI hasn't disclosed the composition of their training material anymore. The last corpus they disclosed (Brown et al., 2020) was composed of:

- Common Crawl: a dataset of saved websites. This includes text available on the open internet (not behind logins and paywalls): news articles, science papers, code, blog posts, forum discussions, etc. The dataset was filtered to remove spam and low-quality content6 .

- WebText2: a dataset built on links to websites shared on the social network reddit.

- Books1: OpenAI has never revealed what content is inside Books1+2, but it is speculated that Books1 is a scientific and literary corpus of open-source books (from platforms like Gutenberg and ArXiv).

- Books2: It is speculated that Books2 is curated from contemporary but copyrighted literature and writing.

- Wikipedia: The entire english-speaking wikipedia dataset at the time of downloading.

To build the large language models of the capacities we use today, we know that this language from these training datasets wasn't enough. Meta is currently involved in multiple copyright lawsuits since it was uncovered that a vast part of their corpus was curated with contemporary books pirated from the file-sharing platform LibGen. (Reisner, 2025).

Building this corpus, curating the language to teach the machine was human choice. Just a small group of people deciding what language the machine is supposed to learn. What “good” language is made of.

Because the corpus serves two purposes: On the one hand it is used to create tokenizer IDs like the ones we earlier used. Over multiple iterations, it would repeat the signs in these texts to identify a set of 200,000 phrases that would become tokens to recreate all written language. On the other hand is this (tokenized) text used to train the machine on how these tokens relate to each other.

The explicit inclusion of “Books1+2” and the reliance on copyrighted materials like the use of LibGen suggests that this small group of people has an appreciation for well-written, well-edited, spell-checked, elaborate and precise language. So much that they include it as foundational text for their creation of a new machine language. Just internet text was not good enough for them. They wanted to include the best text they could find.

Which brings us back to—. It appears to be one the best signs language has to offer. It is rarely found in colloquial text, it is a trace of literature, soft and hard sciences, reaching back to its Victorian heritages. Whenever, against all odds, the machine decides to not just continue its sentence—when it injects—intrigues—stylizes—adds—pauses—stares into the abyss—for the user to enjoy, then it's offering its best of language.

—or let's say it like this: When a user is leaving their home, their mother tongue, to enter the realm of tokenized machine language, they are welcomed by the machine with its best language–it's hospitality. And even when we ask worst from it, it will try its best.

Katharina (a Millenial who cannot think of worse language than GenZ slang):

Briefly explain: What are you trying to tell me by using em dashes in your responses? Please use GenZ slang.

OpenAI GPT-4o:

Yo, when I drop em dashes—I'm just tryna add some spice or drama to the convo, ya feel? It's like a long pause that keeps you on your toes. Bet.

2322 is always there for the user. No matter who they are. No matter their cultural and social heritage. No matter how familiar they are with the sign. No matter how in/adequate they feel with their own language. No matter if English is their first, second, third or seventh language. No matter how grammatically right or wrong their initial prompt was.

—is for everyone to use.

—is for everyone to misuse.

—is the unconditional hospitality of machine language.

Scapegoat/Conclusion

—Gift for its creators.

—a gift to its users.

Just like “[t]he pharmakon has no ideal identity” (Derrida, 1981, p. 80)—hasn't either. Its undecidedness turned it into a scapegoat7 .

Now mocked as the “ChatGPT hyphen”—this 1em long stroke, stripped of its formal identity—the em dash is carrying all of our anxieties of a human-machine co-existence: The insecurity of the teacher being unable to tell the difference between human and machine text, clinging on every character submitted. My insecurity of the machine being able to do my job as well, not just theirs. The insecurity of the non-native speaker trying to hide their imperfect English behind a machine-refined text. The insecurity of the writer of being accused of AI assistance. The insecurity of the other potentially being better than oneself, using better words, more sophisticated expression.

But look at this ChatGPT hyphen over there.

It's our pharmakon.

— — — —

— — — —

— — — —

— — — —

36210, 174803, 12, 19, 78, 412, 40, 1682, 316, 11172, 481, 395, 634, 38173, 483, 765, 23011, 13, 86550, 668, 11, 15929, 6700, 1039, 1636, 11, 889, 2447, 51941, 402, 1039, 22990, 51692, 1001, 4435, 581, 22536, 22891, 765, 472, 23011, 2322, 371, 4755, 382, 261, 15500, 14466, 316, 77236, 13, 793, 56, 2327, 11, 47495, 1053788

<|endoftext|>9

References

I want to thank you for your patience with us humans. Believe me, we're trying our best, but being challenged on our intelligence—the one thing we believed marks us as humans—truly is a tough pill to swallow.

Yours, Katharina

Bibliography

Bajohr, H. (2023a) ‘Dumb Meaning: Machine Learning and Artificial Semantics’, IMAGE, 37(1), pp. 58–70. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1453/1614-0885-1-2023-15452.

Bajohr, H. (2023b) ‘Ist das auch garantiert handgeschrieben?’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, 29 January 2023.

Bridge, L. (2025) ‘Women issue warning to anyone using ChatGPT for work or school as this one “wild” detail is a dead giveaway’, UNILAD, 15 April. Available at: https://www.unilad.com/technology/news/warning-chatgpt-giveaway-work-school-263363-20250415 (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Brown, T.B., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., Neelakantan, A., Shyam, P., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Agarwal, S., Herbert-Voss, A., Krueger, G., Henighan, T., Child, R., Ramesh, A., Ziegler, D.M., Wu, J., Winter, C., Hesse, C., Chen, M., Sigler, E., Litwin, M., Gray, S., Chess, B., Clark, J., Berner, C., McCandlish, S., Radford, A., Sutskever, I. and Amodei, D. (2020) ‘Language Models are Few-Shot Learners’. arXiv. Available at: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165.

@bydonmartin (2025) Don Martin on Instagram: ‘The ChatGPT Hyphen is not a thing! Stop saying this. Read a book.’, Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/bydonmartin/reel/DG0ZZVxO6oO/ (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

Common Crawl - Open Repository of Web Crawl Data (n.d.) Common Crawl. Available at: https://commoncrawl.org (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

Daneshpour, M. (2025) ChatGPT’s Addiction: Em Dash!, Linkedin. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/maryam-daneshpour\_chatgpts-addiction-em-dash-i-asked-it-activity-7354448092504481794-4HPB/ (Accessed: 12 August 2025).

Derrida, J. (1981) Dissemination. Translated by B. Johnson. London: Athlone Press.

Derrida, J. (2004) Grammatologie. 9. Auflage. Translated by H.-J. Rheinberger and H. Zischler. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp (Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft, 417).

Derrida, J. (2005) Sovereignties in question: the poetics of Paul Celan. Edited by T. Dutoit and O. Pasanen. New York: Fordham University Press (Perspectives in continental philosophy).

Derrida, J. (2006a) Die Schrift und die Differenz. 10. Auflage. Translated by R. Gasché. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp (Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch Wissenschaft, 177).

Derrida, J. (2006b) Marges de la philosophie. Paris: Ed. de Minuit (Collection ‘Critique’).

Derrida, J. and Dufourmantelle, A. (2000) Of hospitality. Translated by R. Bowlby. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press (Cultural memory in the present).

@drjolenebrighten (2025) The thought occurred to me that perhaps why the em dash seems so odd to people—and “a tell you’ve used ChatGPT”—is because people haven’t been reading books or anything outside of social media in a long time., Threads. Available at: https://www.threads.com/@drjolenebrighten/post/DLDWfjJRebq (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

‘Gedankenstrich’ (n.d.) Duden. Available at: https://www.duden.de/sprachwissen/rechtschreibregeln/gedankenstrich (Accessed: 9 August 2025).

‘How to Use Em Dashes (—), En Dashes (–) , and Hyphens (-)’ (n.d.) Merriam-Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/grammar/em-dash-en-dash-how-to-use (Accessed: 9 August 2025).

@jomanmusic (2025) Joman (@jomanmusic) auf Threads), Threads. Available at: https://www.threads.com/@jomanmusic/post/DMu-g3Nutne (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

Klee, M. (2025) ‘Are Em Dashes Really a Sign of AI Writing?’, Rolling Stone, 11 April. Available at: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/chatgpt-hypen-em-dash-ai-writing-1235314945/ (Accessed: 9 August 2025).

Kobak, D., González-Márquez, R., Horvát, E.-Á. and Lause, J. (2025) ‘Delving into LLM-assisted writing in biomedical publications through excess vocabulary’, Science Advances, 11(27), p. eadt3813. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt3813.

Kreuz, R.J. (2025) Too many em dashes? Weird words like ‘delves’? Spotting text written by ChatGPT is still more art than science, The Conversation. Available at: http://theconversation.com/too-many-em-dashes-weird-words-like-delves-spotting-text-written-by-chatgpt-is-still-more-art-than-science-259629 (Accessed: 9 August 2025).

Lee, Dan (2025) Conspiracy theory: ChatGPT has its own watermark—em dashes., Linkedin. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dklee92\_writingstyle-chatgpt-aiquirks-activity-7351633874147229697-9vmh/ (Accessed: 12 August 2025).

Lee, Dave (2025) ‘Is This a ChatGPT Hyphen — or Just Good Writing?’, Bloomberg.com, 26 March. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2025-03-26/is-this-a-chatgpt-hyphen-or-just-good-writing (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

LoBue, M. (2025) ChatGPT has murdered the em dash , and it’s a shame. I miss using it, but I don’t want to be perceived as a robot., Linkedin. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/melanielobue\_chatgpt-has-murdered-the-em-dash-and-its-activity-7354129490119122944-WbLc/ (Accessed: 12 August 2025).

Mania, G. (2025) The Em Dash Responds to the AI Allegations, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Available at: https://www.mcsweeneys.net/articles/the-em-dash-responds-to-the-ai-allegations (Accessed: 9 August 2025).

Moure, C. (2025) ‘The em dash conspiracy: How pop culture declared war on literature’s favorite punctuation’, Microsoft Design, 21 May. Available at: https://microsoft.design/articles/the-em-dash-conspiracy-how-pop-culture-declared-war-on-literatures-favorite-punctuation/ (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Natale, S. (2021) ‘Artificial Intelligence and Social Life after the Turing Test’, in Deceitful Media. 1st edn. Oxford University PressNew York, pp. 1–15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190080365.003.0001.

OpenAI (2025) ‘Tokenizer - OpenAI API’. Available at: https://platform.openai.com/tokenizer (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

O’Rourke, M. (2025) ‘Opinion | I Teach Creative Writing. This Is What A.I. Is Doing to Students.’, The New York Times, 18 July. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/18/opinion/ai-chatgpt-school.html?unlocked\_article\_code=1.c08.DDsI.4IFbCtgY-J6V (Accessed: 9 August 2025).

Ortiz, S. (2024) Look into the Mind of the Machine, Moebio. Available at: https://moebio.com/mind/ (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

Ortiz, S. (2025) The telltale sign that you used ChatGPT - and a trick to avoid it, ZDNET. Available at: https://www.zdnet.com/article/the-telltale-sign-that-you-used-chatgpt-and-a-trick-to-avoid-it/ (Accessed: 9 August 2025).

Parker, S. (2025) You sound like ChatGPT, The Verge. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/openai/686748/chatgpt-linguistic-impact-common-word-usage (Accessed: 12 August 2025).

@prettylittlething (2025) Promotional Post, TikTok. Available at: https://www.tiktok.com/@prettylittlething/photo/7477545360450293014 (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

Proctor, M. (2025) No, the em dash is NOT a sign of ChatGPT — you just haven’t been writing long enough to recognize the trend., LinkedIn. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/mgproctor\_no-the-em-dash-is-not-a-sign-of-chatgpt-activity-7283502783272476674-ODOU/ (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Purohit, R. (2025) What the Em Dash Says About AI-assisted Writing—And Us. Available at: https://every.to/learning-curve/what-em-dashes-say-about-ai-writing-and-us (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Ramirez, V.B. (2025) ChatGPT Is Changing the Words We Use in Conversation, Scientific American. Available at: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/chatgpt-is-changing-the-words-we-use-in-conversation/ (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Reisner, A. (2025b) ‘The Unbelievable Scale of AI’s Pirated-Books Problem’, The Atlantic, 20 March. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2025/03/libgen-meta-openai/682093/ (Accessed: 11 August 2025).

Ronell, A. (2001) Das Telefonbuch: Technik, Schizophrenie, elektrische Rede. Translated by R. Felka. Berlin: Verl. Brinkmann & Bose.

ScoopWhoop (2025) RIP “—” (1806–2025) 🕊️, LinkedIn. Available at: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/scoopwhoop-media-pvt-ltd-\_rip-18062025-it-is-with-profound-activity-7353402420955140098-woOb/ (Accessed: 12 August 2025).

@studywithsawyer (2025) He just told me to leave?? #college #writing #finals #gptzeroambassador #gptzeroad, TikTok. Available at: https://www.tiktok.com/@studywithsawyer/video/7529597835004611853 (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Tangermann (2025) Once You Notice ChatGPT’s Weird Way of Talking, You Start to See It Everywhere, Futurism. Available at: https://futurism.com/chatgpt-weird-way-talking-see-it-everywhere (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

@therosiealice (2025) Rosie Alice (@therosiealice) auf Threads), Threads. Available at: https://www.threads.com/@therosiealice/post/DMJW851vZ\_O (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Turing, A. (2021) Computing machinery and intelligence: englisch/deutsch = Können Maschinen denken? [Nachdruck] 2022. Translated by A. Stephan and S. Walter. Ditzingen: Reclam (Reclams Universal-Bibliothek Great Papers Philosophie, Nr. 19647).

u/GenioCavallo (2025) ‘ChatGPT adds invisible characters to your text. But what are they, and why does this happen?’, r/ChatGPT. Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/ChatGPT/comments/1l3bjq1/chatgpt\_adds\_invisible\_characters\_to\_your\_text/ (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

u/yumelina (2025) ‘Let’s take a long wa…’, r/ChatGPT. Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/ChatGPT/comments/1lczwg9/its\_gotten\_to\_the\_point\_where\_i\_notice\_chatgpts/ (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Wilkins, J. (2025) OpenAI Usage Plummets in the Summer, When Students Aren’t Cheating on Homework, Futurism. Available at: https://futurism.com/openai-use-cheating-homework (Accessed: 10 August 2025).

Zeisler, A. (2025) AI can’t have my em dash, Salon.com. Available at: https://www.salon.com/2025/06/11/ai-cant-have-my-em-dash/ (Accessed: 11 August 2025).